Scholars’ Study #2

We are pleased to circulate the second edition of our Scholars’ Study eNewsletter. The aim is to inform our community about publications, events, or other news in relation to the scholars and more widely to psychoanalysis beyond the clinic. The eNewsletter should facilitate a home and community for the Scholars where we can all share ideas, get to know each other, and learn about events, or other activities.

It is managed by the Editors, Dr Theodora Thomadaki (University of Roehampton) and Dr Jacob Johanssen (St. Mary’s University), with Associate Editors: Amy Tatum (Bournemouth University), Ruth Llewellyn, and Michael Clarke (University of Roehampton). Please email Theodora and Jacob if you would like to be involved.

CONTENTS:

Texts from our Scholars:

- Paul Sutton: On Lockdown

- Dr Deborah Wright: Room-object Spatialising in the Time of COVID-19: The Physical Space and the Remote, Virtual/Online Space of the Consulting Room

- Brett Kahr: Professor Robert Maxwell Young (1935-2019): A Champion of Bravery and Intellect

- Brett Kahr: Lloyd deMause (1931-2020): The Father of Psychohistory

- Professor Lesley Caldwell

- Dr Zack Eleftheriadou

- Dr David Henderson: Comparative Psychoanalysis Research Group

- Dr Jacob Johanssen: Social Media in Times of Coronavirus: A Paranoid-Schizoid Pandemic?

- Dr Theodora Thomadaki: How to Look Good Naked ‘On the Couch’

- Professor Candida Yates: Special Issue of Free Associations: ‘Psychosocial Reflections on 50 Years of Cultural and Political Revolution’

- Caroline Zilboorg

- Confer Books

- Association for Psychosocial Studies (PCS)

- APS and the Journal of Psychosocial Studies Online Reading Group

- Association for the Psychoanalysis of Culture & Society (APS): Annual Conference and Journal

An Interview with BPC Scholar Professor Barry Richards (Bournemouth University)

1) How did you first encounter psychoanalysis?

My first direct encounter was probably in an optional unit in my psychology degree called ‘Abnormal psychology’. It included a respectful presentation of some classical Freudian theory, and I must have ‘bookmarked’ it as an area to look into some more. At least I got through the degree without acquiring the prevalent view that Freud was an old curiosity that real psychology had moved on from, a belief mechanically fed over the generations to psychology students all over the world.

2) Why did you decide to become a clinician / scholar who draws on psychoanalysis?

I didn’t properly get into psychoanalysis until I was doing a clinical psychology training. At that time (the early 1970s), in Britain these trainings were organised by health authorities not universities, and I was based at Shenley Hospital just outside north west London. Long since a housing development, this was then one of the large asylums found on the edges of large cities, the ‘loony bins’ of popular imagination. I had applied there knowing it to be where David Cooper, a collaborator of Ronald Laing, had worked, and my interest in clinical work had been inspired by Laing’s writings. As I was to discover, it was a fairly conventional mental hospital, with a very limited capacity to offer real ‘asylum’ amidst its more custodial functions, but its Psychology Department had longstanding links with the Tavistock Clinic and the London psychoanalytic community.

So my training included a major encounter with ‘British’ psychoanalysis; I think a definitive experience for me was reading the work of Harry Guntrip, followed by immersion in Klein, Fairbairn and Winnicott. Never mind all I had learned as an undergraduate about evidence and objectivity: this was a different and much deeper kind of knowledge, that articulated emotional truths about my own and other people’s experiences, and made sense of some things that otherwise seemed without meaning.

3) What is the role of psychoanalysis in the clinical sphere and beyond, both today and in the future?

I was never entirely comfortable as a clinician, and after some years I left clinical work for academia, so I can’t comment from the inside on psychoanalysis in the clinical sphere. I just hope that since psychoanalysis offers the most sophisticated and profound language we have for thinking about mind and self, then ways of thinking and working based on it will have a growing presence in therapeutic practices of all kinds, from intensive long-term work to short-term counselling and crisis work, and on into the everyday practices of health care, social care and social work. Beyond all that, there is also the question of how approaches drawing on psychoanalytic insights, combined with other forms of understanding, can help us to understand developments in wider society, especially in the political sphere since that is where policies of all sorts are determined.

There are several major impediments to all this. One is the antipathy and resistance to psychoanalysis, which its supporters have had to deal with from Freud onwards. Another is practical: psychoanalytic expertise is still a very rare resource, globally, and is associated with long-term and expensive ways of tackling problems, though its potential contributions are not necessarily resource-hungry. And another is the difficulty for some psychoanalytic communities to orient themselves to the world outside their own practices and institutions, and to find ways of speaking and writing that do not seem esoteric or weird to a great many people.

4) What would you like the BPC Scholars community to be like?

Open-minded, purposeful and unpretentious. That could mean various things in practice. A few projects in which some scholars could get involved, and others would be interested to follow, could be the heart of it, with the Newsletter as the connecting thread. The ‘Politics from the Couch’ idea, which I proposed at the end of last year, has led to a couple of meetings but it has not yet become clear that it will take root. The idea was for clinicians and academics to meet every so often to consider clinical material involving some political content (e.g. clients’ dreams about or associations to political issues or politicians), to see if this offered a new way of throwing psychoanalytic light on political matters. The third meeting was postponed owing to the pandemic, though will be reconvened (probably online) in the early autumn. There seems to be an appetite amongst academics for this idea; the question is probably going to be whether sufficient clinicians see enough value in it to take part. It may mutate into a more general type of ‘psychoanalysis and politics’ discussion group. Whatever happens to this particular initiative, the fact that we have all been bumped into online meetings, and seen how they can bring people together easily across large distances, is likely to facilitate the establishment of reading groups, workshops and so on.

5) What are your thoughts on the current Coronavirus crisis in the UK and globally?

For one thing, many of those who have been able to work online have been able to see how little their core activities depend on physical co-presence, and there are predictions that home working, in its ultra low-carbon comfort and convenience, will become integral to many post-pandemic business models. On the other hand, as I write (in June 2020) I seem to be hearing more reports of being Zoomed out, of the fatigue and frustration generated by the hours of screentime with others that is actually not fully with them. Psychoanalysis has things to say about that about the physical presence or absence of the object.

More broadly, this pandemic is the most global thing ever, and the most potentially unifying, notwithstanding the fact that within nations it impacts very differently on different socio-economic and ethnic groups. But for me it is too early to be talking about where it is taking us, about, for example, whether it will be a helpful stimulus to a revaluation of our heavily-consumption-based lives, or of any other aspects of the ‘old normal’.

In most countries it should in one way or another make some difference to people’s ideas and feelings about the state. A pandemic is a situation in which the reality of our dependence on the state is laid bare. The speed with which huge emergency hospitals were created, and then the massive scale of the furlough scheme, demonstrate the unique power of the state to intervene effectively in a protective way, and the irrelevance of market-based doctrines to the core functioning of human societies in crisis.

6) What are your reflections on the psychodynamics of the emotional governance and self-surveillance that have been implemented as a social measure by the government as a way to ‘flatten the curve’?

At the same time as we have all witnessed our need for the state, and those examples of it responding beneficiently, we have also seen members of this particular government showing contempt for the truth, and thereby for the public they expect to believe them, on key aspects of their strategy such as the timing of the lockdown, the scale of testing and the re-start of track & trace (not to mention the Cummings affair). Sadly that is what we should always expect from this Prime Minister. More surprising is the way in which the in-house senior scientists seem to have contributed to or acceded to some very bad decisions. I’m afraid I have not been able to trust anything either the Chief Medical Officer or the Chief Scientific Advisor say since watching them at one of the earlier daily briefings explain why it was necessary to establish herd immunity (incredibly, a strategy later disavowed). The key psychodynamic issue in a situation like this is going to be trust, in government and in expertise. The global spread of populist and polarising politics has deepened the already strong distrust of government, and of scientific expertise as well. The relative diversity of expert opinion on pandemic matters, while inevitable, does not help in his regard. We like scientists to agree. Again, perhaps I’m being a bit slow, but I doubt we can yet see how all this is going to pan out.

7) Can you tell us about any projects you are currently working on?

I’m continuing to work on various aspects of politics viewed psychosocially as the mobilisation of feelings and of unconscious phantasies across social groups and national publics. In particular the internal and external drivers of polarisation and extremism on the one hand, and of social cohesion on the other, are my major themes. I think liberal representative democracy is a very demanding form of polity, in terms of what it asks emotionally of its citizens, and therefore psychoanalytic political psychology has a lot to contribute in understanding why it is so difficult – and increasingly so – for democracies to work well. I am presently looking at changes over time and between nations in levels of trust in government, and their relationship to other variables. I have been arguing for some time that national identity has a key positive part to play in strengthening democratic processes.

I am also keen to see the results of the natural experiment that has just begun in testing the importance of the crowd in the home advantage in professional football. It will be a surprise if the absence of the power of shared feeling, of the intense kind of projective belonging that football crowds evoke, makes no difference.

Texts from our Scholars

Paul Sutton: On Lockdown

Although the Coronavirus lockdown in England has begun to ease a little over the

past month, any return to the past that we are all used to still seems more or less impossible. Many of us, I suspect, are feeling a certain kind of nostalgia or mourning, for the lives that we used to lead. In some cases, this represents something utterly fundamental, the consequences of which are far reaching and tragic: a loss of lives, livelihood, income, identity and meaning. In others it might simply be the routine that had come to define the life we lived. We lament the loss of a whole range of activities planned for the future, from the day to day to the more long term: the ability to physically express our love for friends and family, the holidays no longer to be taken, the celebrations at the end of the school year and the long summer that our school children had so looked forward to, to name but a few…

Time in lockdown is stretched out, it is almost as if it has melted in a surreal Daliesque fashion. We remain stuck in a continual present while experiencing

simultaneously a loss of the past and a mourning for the future, one that we can

barely conceptualise at the moment. Freud famously described mourning as ‘the

reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, an ideal, and so on’ (‘Mourning and Melancholia’ 1917 [1915]: 252). Our loss of liberty, along with the ideal of trust in those who represent our country, our government, certainly describes the losses that one might associate with this period of lockdown. Freud reflects further on mourning and loss in his short paper ‘On Transience’ (1916 [1915]), where he combines mourning with transience. He describes an episode in which a poet and a friend are unable to enjoy a scene of beauty because, as Freud surmises, ‘[t]he idea that all this beauty was transient was giving these two sensitive minds a foretaste of mourning over its decease’ (1916: 288).

Thinking about our current situation, it is precisely the ‘foretaste’ that is significant here because it suggests a projection into the future that is then read back, by an effect of afterwardsness, into the present, thus altering it. Transience articulates the projection or the figuration of loss in the future, which is then turned back on the present moment to provoke the experience of loss in the present. Transience is the experience in the present of a future loss, it is the perception of potential loss in the future through the recollection, a coming into consciousness of, prior, unconscious loss from the past. This temporal and memorial dynamic seems to describe well the experience of the Covid 19 lockdown. Our lives are being lived in the moment, in a perpetual present in which both the past and the future appear lost, subject to the ache of mourning. As a film scholar interested in psychoanalytic theory it is the cinema that I miss. I long for the collective experience that my local repertory cinema provides. I mourn the loss of the post-screening discussions that I used to lead with its generous, cinephile audience. I miss the strange intimacy that is the cinema. We have to hope that this health crisis will ultimately prove transient and that we will once again be able to return to lives that although inevitably altered will once again be able to be lived to their fullest. Roland Barthes in a mournfully beautiful essay entitled ‘On Leaving the Cinema’, describes the curative effects of the cinematic encounter. In closing, his words feel somehow entirely apposite:

‘he walks in silence (he doesn’t like discussing the film he’s just seen), a little

dazed, wrapped up in himself, feeling the cold – he’s sleepy, that’s what he’s

thinking, his body has become something sopitive, soft, limp, and he feels a

little disjointed […]. In other words, obviously, he’s coming out of hypnosis. And

hypnosis (an old psychoanalytic device – one that psychoanalysis nowadays

seems to treat quite condescendingly) means only one thing to him: the most

venerable of powers: healing’ (1979: 1).

References:

Barthes, R. (1979) Upon Leaving the Movie Theater. Trans. Augst, B., and White, S. In: Cha, T. H. K. (ed.) (1980) Cinematographic Apparatus: Selected Writings. New York, Tanam Press, pp. 1-4.

Freud, S. (1973-86) The Penguin Freud Library. Trans., and under the general

editorship of Strachey, J., and ed. by Richards, A., and Dickson, A., 15 vols. London, Penguin. [PFL]

Freud, S. (1916 [1915]) On Transience. In: Art and Literature. PFL, 14, pp. 283-90.

Freud, S. (1917 [1915]) Mourning and Melancholia. In: On Metapsychology: The

Theory of Psychoanalysis. PFL, 11, pp. 245-68.

Texts from our Scholars

Dr Deborah Wright – Room-object Spatialising in the Time of COVID-19: The Physical Space and the Remote, Virtual/On-line Space of the Consulting Room

I am considering here the spacial aspects of working in the remote virtual/on-line consulting room space, in the time of COVID-19, with reference to my research on the physical space of the consulting room. My research originated from my observation of phenomena relating to patients’ relationships with the consulting room, where they project onto the room, and the spatial array of the space and the margins surrounding the room in a sensory way, at times seemingly unrelated to the transference to me, (following Searles [1960], Wollheim [1969] and Rey [1994] on place meaning). I am calling this room transference (Wright 2018) Room-object spatialisation. The term ‘spatialisation’ (Shields 1991) has been used to describe social meaning related to spaces. I use the term ‘spatialisation’ (Wright 2019), not only for the purpose of ascribing meaning to space, but also to refer to the psychological and physical mechanisms by which this happens, as well as for the motivation behind its use. Spatialisation simultaneously involves a psychological projection of meaning and physically acting upon the environment, utilised to master the undifferentiated, relentless, internal pressure of instinct (Freud 1915). I suggest that this can take place within a matrix of stages, the first of which takes place into mother/parts of mother to create the object, this is pre-object and therefore pre-transferential. I suggest that a difficulty in utilising mother as the first object of spatialisation, can lead to spatialising into the spatial array of room spaces and the objects within them which replaces or supplements the mother function. Sigmund Freud described in metaphorical terms that ’a room became the symbol of a woman as being the space which encloses human beings’ (Freud 1916). The consulting room can be used as other rooms (Figure 1) were used before as a direct displacement from one room to the other, separate from transference to the therapist. or including it and this can be re-spatialised into other room spaces.

Figure 1: The Spatial Array of a Building Introjected as an Auxiliary Mind, Painting (D. Wright)

In the COVID-19 remote psychotherapy, patients have had to be creative in their spatialising outside the consulting room space; forming their own couches, chairs and spaces. The patients with less reliable objects/room-object may have had more difficulty with this transition. One such patient said to me during her second online session. “Where does all the stuff go when we are not in the room? The stuff usually stays in the room. Where is it now?” and gestured around in the air with her hand. Figure 2 shows two separate room spaces where everything might get lost in the black hole of the middle of the room spaces.

Figure 2: Online working in room spaces, Painting (D. Wright)

Figure 3 shows a virtual room involving a degree of introjection of room-object spatialised ‘mirroring’ (Winnicott 1967) as well as the consulting room re-spatialised in the imagination.

Figure 3: The Virtual On-line Consulting room space, Drawing (D. Wright)

It might be considered then, that patients who have never been in the room at all and manage to work remotely from the beginning, as I have found starting remote working with a new patient this week, might have a reasonably formed object/room-object introjection in order to engage with the work in this way; a scholarly work in progress- watch this space.

References:

Freud, S. (1957 [1915]). Instincts and their Vicissitudes. Tr. & ed. James Strachey et al. Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol XIV. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis. 109-140.

Freud, S. (1963 [1916]). Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. Tr. & ed. James Strachey et al. Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol XV. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis. (Part I&II) 1-240.

Rey, J. H. (1994) Universals of Psychoanalysis in the Treatment of Psychotic and Borderline States. Free Association Books.

Searles, H.F. (1987[1960]) The Nonhuman Environment In Normal Development and in Schizophrenia. Madison Connecticut: International Universities Press., Inc.

Shields, R. (1991) Places in the Margin: Alternative geographies of modernity. London: Routledge.

Winnicott, D W (2002 [1967]) Mirror-role of Mother and Family in Child Development. [First published 1967] Playing and Reality. London: Routledge. (1971, reprinted 2002), p111-118.

Wright, D., (2018) Rooms as Replacements for People: The Consulting Room as a Room Object. In: On Replacement – Cultural, Social and Psychological Representations. Editors: Owen, J. and Segal, N., Palgrave Macmillan

Wright, D., (2019). Spatialisation and the Fomenting of Political Violence. In: Fomenting Political Violence – Fantasy, Language, Media, Action. Editors: Kruger, S., Figlio, K. and Richards, B. Palgrave Macmillan

Wollheim, R. (1969). The Mind and the Mind’s Image of Itself. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 50:209-220.

Dr Deborah Wright is a psychotherapist (BPC, FPC, MBACP) and a lecturer in the Department of Psychosocial and Psychoanalytic Studies, University of Essex. She is a trained Artist and her art-work and academic research relates to human’s relationships with their environment – rooms, places and spaces. She is currently writing a book on room-object spatialising in the consulting room and virtual consulting room spaces.

Texts from our Scholars

Brett Kahr: Professor Robert Maxwell Young (1935-2019): A Champion of Bravery and Intellect

On 5th July, 2019, the psychoanalytical community lost one of its most substantial members, the remarkably brilliant Professor Robert Maxwell Young – a pioneering clinician and scholar – who died in hospital at the age of eighty-three years.

Across a long and distinguished career, Robert Young, known universally as “Bob”, worked tirelessly to promote mental health and psychoanalysis, both inside and outside of the consulting room. A consummate clinician and supervisor who treated a wide range of patients, Bob also made an immense contribution to the professions of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy as a scholar, a teacher, and a writer, and, moreover, as a journal editor, a university professor, and, most impressively, as a publisher.

Born in Highland Park, a suburb of Dallas, Texas, on 26th September, 1935, Bob Young studied at both Yale University and at the University of Rochester before emigrating to the United Kingdom in order to complete his doctoral degree in the history of science at the University of Cambridge, concentrating on the cerebral localization of brain functioning during the nineteenth century. Young soon became a fellow at King’s College in the University of Cambridge and earned an influential post as the inaugural director of the university’s Wellcome Unit for the history of medicine. During that time, he published a landmark book on the history of neuroanatomy and neurobiology, the now classic Mind, Brain and Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century: Cerebral Localization and its Biological Context from Gall to Ferrier (Young, 1970).

Eventually, Young gravitated towards the field of psychotherapy, and he gradually retrained as a clinician in his own right after having undergone a lengthy period of psychoanalysis. But in spite of having transplanted himself from an office in one of the most luxurious of Cambridge colleges to the more austere setting of a consulting room in North London, Young never abandoned his deeply-internalised academic and scholarly temperament, or his erudition, or, indeed, his critical capacities; and, happily, he rewarded the psychoanalytical profession by sharing his unique wealth of knowledge.

In 1984, Young embarked upon a parallel career as editor of a new psychoanalytical journal, Free Associations, and as progenitor of a new imprint, Free Association Books. One must recall that, back in the 1980s, the British psychotherapy world boasted very few opportunities for publication. Neither the British Journal of Psychotherapy nor Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy had yet appeared in print, and publishers such as H. Karnac (Books) Limited produced predominantly reprints of older psychoanalytical classics. Through the creation of a new journal and a new publishing house, Bob Young took a great risk – and a courageous one – in expanding the opportunities for clinicians and scholars alike to share their researches more broadly. In this respect, he egalitarianised the psychoanalytical profession immensely.

As a young student, I relished each new edition of Free Associations as I found the articles printed therein deeply refreshing and challenging and, moreover, such a delightful contrast to the somewhat more stuffy and sectarian essays published in the rather traditional periodicals. I also began to purchase the stream of wonderfully creative titles produced by Bob’s press, Free Association Books, not least Capitalism and Infancy: Essays on Psychoanalysis and Politics, edited by the clinical psychologist Dr. Barry Richards (1984) (subsequently Professor Barry Richards) – a wonderful collection of chapters exploring the rich and complex interrelationship between Freudian theory and the political sphere. Although nowadays it seems as though everyone has become an expert on the intersection between psychoanalysis and politics, during the 1980s this book broke truly new ground.

If memory serves me correctly, at some point in 1984, I wrote a “fan letter” to Bob Young, congratulating him on his new journal and his new press. At that time, I had established a weekly lecture series, The Oxford Psycho-Analytical Forum, endeavouring to promote psychodynamic thinking in a university overrun by behaviourists and pharmacologists. Bob warmly encouraged me in my pursuit. He also asked whether I might help him to publicise his journal Free Associations among members of the Oxford community. (Back then, we had no e-mails or Twitter accounts or internet; thus, if one wished to promote a new publication, one had no option but to produce innumerable flyers and then place them into stamped envelopes before depositing them in a Royal Mail letter box). Naturally, I agreed to offer whatever assistance I could, and, within a matter of days, Bob posted an entire crate of publicity materials to me – perhaps as many as 1,000 press releases – and I shall never forget how I then spent an entire monotonous evening folding innumerable flyers and licking a seemingly endless number of stamps in order to advertise Bob’s extremely worthy publishing venture.

Bob appreciated my efforts on his behalf, and, in gratitude, he kindly invited me to attend the launch party of Free Association Books at his home on London’s Freegrove Road. Although a mere student at that time – somewhat full of trepidation – I accepted Bob’s gracious offer of hospitality and I then spent a most enjoyable evening hobnobbing with some amazing personalities, many of whom had already signed up to become Free Association Books authors, such as the glamorous French psychoanalyst Madame Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel, whose work I had already come to admire.

In the years which followed, I had the true privilege of meeting Bob in many different contexts – on committees, on panels, and at conferences – and I always learned a great deal from him, no matter what the subject. I found the range and the depth of his mind always quite outstanding, and I deeply admired his capacity to speak frankly and honestly and in a full voice.

When Bob discussed his clinical work with patients, he struck me as a true relational psychoanalyst avant la lettre, always speaking about his analysands with compassion and engagement. He boasted a tremendously well-developed sense of empathy; and I shall never forget his detailed descriptions of the way in which he would always scrutinise his countertransference reactions in order to discover some important insights about split-off unconscious aspects of the psychic lives of his patients.

By contrast, when Bob spoke about his colleagues – and he did so frequently – he rarely pulled his punches. If he regarded a fellow clinician or academic as envious and sadistic, he had little hesitation in issuing a warning, advising the rest of us to be duly wary of that person.

As Bob always communicated with great honesty and with full frankness – a true American from the deep South – he sometimes offended many of his British colleagues who preferred to gossip behind people’s backs. But Bob always expressed his discontent with aspects of the profession in a more direct and engaging way. In fact, he frequently shared his significant reservations about the British mental health community in his public writings and talks. For instance, he even wrote a paper entitled “Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy: The Grand Leading the Bland” (Young, 1997), in which he challenged what he regarded as the elitism of the more conservative and often grandiose members of certain psychoanalytical organisations and the ways in which other members of the profession would idealise such practitioners, thus encouraging a huge split between “psychoanalysts” and “psychotherapists” as a true reinforcement of the centuries-long class system so endemic to British culture.

Bob always championed a more unified and integrated profession. Indeed, if one scans the early issues of his journal, Free Associations, one certainly comes to appreciate very quickly the way in which he recognised that one need not be a psychoanalyst to make a solid contribution to psychoanalysis. Bob encouraged writings from psychotherapists, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, artists, academics, independent scholars, and, also, patients themselves. He created a truly broad church of participants and he welcomed anyone and everyone with serious capacities, maintaining solid, intellectual standards above all else.

As his career progressed, he worked hard to spread psychological knowledge as widely as possible through publishing, having launched not only Free Association Books but, also, Process Press; and, moreover, he blessed the profession through the creation of his generous free website “Human Nature”, on which he would post copies of his articles long before it became standard practice to do so. Additionally, he received a professorship at the University of Sheffield and supervised the doctoral dissertations of many colleagues who have since become leaders in the field of psychoanalytical studies and psychosocial studies. Perhaps most blue-sky of all, he spent a considerable amount of time in Bulgaria and became one of the best facilitators of psychoanalytical thinking in that faraway land.

One cannot do justice to the full extent of Bob’s own theoretical and clinical contributions, which deserve a more extended study in their own right. Certainly, I warmly recommend not only his early work on the history of science but, also, his subsequent psychoanalytical book Mental Space (Young, 1994). He also published a very extensive range of titles by other authors which have since become classics, including Dr. Christopher Bollas’s (1987) impactful text, The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known; Dr. Estela V. Welldon’s (1988) incomparably bold book, Mother, Madonna, Whore: The Idealization and Denigration of Motherhood, which challenged the traditional psychoanalytical theory of perversion; Dr. Nina Coltart’s (1992) compelling book of clinical essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem … And Further Psychoanalytic Explorations; Valerie Sinason’s (1992) extraordinarily pioneering study of disability, Mental Handicap and the Human Condition: New Approaches from the Tavistock (now immortalised in a revised, updated edition (Sinason, 2010)); and others too numerous to mention, including Dr. Donald Winnicott’s (1988) posthumously published Human Nature.

I owe Bob Young a tremendous debt of gratitude. Although I never studied with him in a formal sense, I do consider him as a great teacher. I deeply enjoyed his publications, his lectures, as well as his private thoughts and advice. I also benefited greatly from his lovely energy and from his broad creativity.

Bob made everything possible. He did not comport himself in a passive way. When he wished to accomplish something, he simply sat down and undertook each project with little or no inhibition. On one occasion, Bob confessed to me, “Authority is never granted. Authority must be claimed.” I found this to be a profoundly insightful comment and a very facilitating and empowering antidote to the infantile helplessness so characteristic of far too many human beings.

Bob maintained his clinical membership with the British Psychoanalytic Council for many years, but, upon his retirement from working with patients, he quite understandably ceased to his registration. Thus, when we established the Scholars Network of the British Psychoanalytic Council, the committee unanimously approved Bob as a Founding Scholar … and deservedly so. Bob joined our budding group of Founding Scholars and, although rather infirm, he managed to attend the inaugural party at Freud Museum London on 21st February, 2019. Sadly, he died not long thereafter.

Our hearts go out to Bob’s family and friends and colleagues and to his former patients, whose lives he enriched and improved. I consider myself very fortunate to have had the pleasure and the honour to have known this great man and to have learned so much from him on so many levels.

References:

Bollas, Christopher (1987). The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known. London: Free Association Books.

Coltart, Nina (1992). Slouching Towards Bethlehem … And Further Psychoanalytic Explorations. London: Free Association Books.

Richards, Barry (Ed.). (1984). Capitalism and Infancy: Essays on Psychoanalysis and Politics. London: Free Association Books, and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press.

Sinason, Valerie (1992). Mental Handicap and the Human Condition: New Approaches from the Tavistock. London: Free Association Books.

Sinason, Valerie (2010). Mental Handicap and the Human Condition: An Analytic Approach to Intellectual Disability. [Revised Edition]. London: Free Association Books.

Welldon, Estela V. (1988). Mother, Madonna, Whore: The Idealization and Denigration of Motherhood. London: Free Association Books.

Winnicott, Donald W. (1988). Human Nature. Christopher Bollas, Madeleine Davis, and Ray Shepherd (Eds.). London: Free Association Books.

Young, Robert M. (1970). Mind, Brain, and Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century: Cerebral Localization and its Biological Context from Gall to Ferrier. Oxford: Clarendon Press, and London: Oxford University Press.

Young, Robert (1994). Mental Space. London: Process Press.

Young, Robert M. (1997). Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy: The Grand Leading the Bland. Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. [http://www.psychoanalysis-and-therapy.com/human_nature/papers/pap101h.html].

Texts from our Scholars

Brett Kahr: Lloyd deMause (1931-2020): The Father of Psychohistory

Throughout the course of my career, I have had the privilege of meeting many extremely intelligent teachers, colleagues, and students, most of whom have impressed me with their wisdom and erudition and liveliness of mind. But I have encountered only a small handful of people whom I would describe as veritable geniuses, and Lloyd deMause undoubtedly occupies a premier position on that list. Sadly, many British scholars and psychoanalytical clinicians will not recognise the name of Lloyd deMause, as he worked independently and published his own books and journals, but few have, in my estimation, made a greater contribution to the study of trauma and child abuse, and few have enhanced the fields of psychohistory and the history of childhood, as well as the study of psychobiography, and, also, the understanding of political psychology as richly as this remarkable thinker, researcher, and theoretician has done.

Born on 19th September, 1931, in Detroit, Michigan, deMause studied political science at Columbia University in New York City, New York, and then became a research assistant to the noted sociologist Professor C. Wright Mills, before having become a candidate at the New York Center for Psychoanalytic Training. Although psychoanalysed by the leading New York clinician Dr. Reuben Fine, who founded the Division of Psychoanalysis of the American Psychological Association and who wrote an impressive textbook, A History of Psychoanalysis (Fine, 1979), Lloyd deMause elected to focus his own multiple energies upon scholarship rather than upon clinical practice with patients. In fact, deMause became, in many respects, the epitome of the applied psychoanalyst, and he used his deep knowledge of Freudianism to illuminate history and culture and politics with great profundity.

During the l950s and 1960s, very few historians had dared to examine the treatment of children throughout the ages in a serious or detailed manner. Indeed, if one peruses the biographies of historical personalities written in the first half of the twentieth century, one will often be shocked that the chapters devoted to the subjects’ early years frequently occupy no more than a few pages. As Lloyd deMause often noted, back then, long before the emergence of the modern feminist movement, scholars devoted all of their attention to the study of kings and castles; very few examined the history of women, of peasants, and of ethnic minorities, and, certainly, almost no one explored the ways in which adults related to their infants and children.

Aware of this gaping hole in scholarship, deMause collaborated with a small and somewhat marginal group of forward-thinking fellow academics to investigate the history of child care in detail from ancient times to the present day; and, in 1974, he published the remarkable edited book, The History of Childhood (deMause, 1974a), which featured his own landmark chapter on “The Evolution of Childhood” (deMause, 1974b), fully seventy-three pages in length and brimming with detailed notes and references to a remarkable range of sources across many centuries. In this compelling and impactful study, deMause discovered that, during antiquity, a significant percentage of parents would sacrifice their children to the gods – an act that we would now describe purely and simply as infanticide. In subsequent centuries, mothers and fathers would abandon their offspring, beat them mercilessly, and engage in other forms of cruelty. Shockingly, deMause argued that only in the twentieth century did parents begin to treat their children in a more consistently loving manner.

Contemporaneously, deMause launched his very own journal, the History of Childhood Quarterly: The Journal of Psychohistory, which commenced publication in 1973 and which then became restyled, more broadly, as The Journal of Psychohistory in 1976. Happily, this landmark periodical continues to publish creative essays on applied psychoanalysis to this very day.

If one examines the chapters in deMause’s edited book on The History of Childhood and the early papers published in his journal, one readily appreciates the huge contribution that he and his colleagues made to our understanding of the ubiquity of child abuse throughout the ages. These early works proved particularly striking, especially in view of the fact that few mental health professionals in the 1960s and 1970s recognised the widespread nature of parental abuse and cruelty at all.

But deMause did not confine himself to the study of child maltreatment throughout the ages; in fact, he used this historical data as the bedrock for an understanding of broader events and movements throughout the course of humanity. DeMause argued that one simply cannot understand political cruelty and warfare without first appreciating the significance of childhood traumata endured by world leaders and their followers. According to deMause, the history of childhood formed the very bedrock of political psychobiography and, subsequently, of the study of group processes throughout the ages, focusing on the ways in which early experiences of cruelty become repressed in the unconscious and then re-enacted upon the public stage in the shape of global violence.

In an effort to collaborate with open-minded colleagues, Lloyd deMause founded the Institute of Psychohistory in New York City, New York, and hosted regular meetings in his office building on Broadway, discussing his ideas with a pioneering group of scholars and clinicians from a wide range of disciplines. In many respects, the gatherings at the Institute of Psychohistory resembled the early meetings of Professor Sigmund Freud’s Wednesday night study group, which became the foundation of the Wiener Psychoanalytische Vereinigung [Vienna Psycho-Analytical Society] – the world’s very first formal psychoanalytical establishment. And, not unlike Freud, who also launched the Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Vereinigung [International Psycho-Analytical Association], deMause created an I.P.A. of his own, namely, the International Psychohistorical Association – a small, but persistent, global organisation which still flourishes, and which hosts an impressive, interdisciplinary annual conference.

DeMause persevered with his unique research and scholarship. In 1975, he produced another compelling edited book, The New Psychohistory (deMause, 1975a), as well as a very erudite reference work, A Bibliography of Psychohistory (deMause, 1975b). And not long thereafter, he co-edited a book about the American President, Jimmy Carter, entitled, Jimmy Carter and American Fantasy: Psychohistorical Explorations (deMause and Ebel, 1977), which investigated the ways in which Carter’s early childhood experiences contributed to his work in the White House. Building upon these early tomes, deMause then proceeded to produce a magnificent volume of collected papers, Foundations of Psychohistory (deMause, 1982), followed not long thereafter by a psychobiographical and political psychological study of Ronald Reagan, published under the title Reagan’s America (deMause, 1984). Ultimately, he completed a stellar tome, The Emotional Life of Nations (deMause, 2002) – a truly profound and memorable integration of his life’s work. Each of these pioneering texts deserves a Festschrift of its own, and I deeply hope that British psychoanalytical scholars who have not yet enjoyed the privilege of reading deMause will begin to examine these unique, original, and staggeringly insightful psychoanalytical texts which remind one of the boldness and breadth of the early writings of Freud himself.

As an undergraduate, I happened to stumble upon the work of Lloyd deMause, simply by browsing the shelves of my university library. I began to read his writings, and, in due course, I had the privilege of meeting him in person. Within minutes, I became a huge fan. His work on the widespread practice of infanticide in the ancient world impacted greatly upon my clinical training; and when, as a young man, I began to treat chronic schizophrenic patients, I found myself listening to story after story of parents threatening to murder their children. None of my clinical supervisors seemed at all interested in knowing about what I came to classify as “psychological infanticide” (Kahr, 1993, p. 269) and, ultimately, as the “Infanticidal Attachment” (Kahr, 2007, p. 119), but, happily, deMause encouraged me to apply his psychohistorical research on infanticide to my own preliminary efforts in a psychiatric hospital; and it pleases me that I have persevered with these clinical investigations, which have continued to enlighten my understanding in the consulting room to this very day.

In 1992, I invited Lloyd deMause to London to deliver several lectures. Within a short number of days, he spoke to The Parent Infant Clinic, the Portman Clinic, the British Psycho-Analytical Society, and the Association of Child Psychotherapists. In view of deMause’s established track record of compelling publications, each of these organisations embraced the opportunity to host him as a speaker.

The colleagues at The Parent Infant Clinic, a small and forward-thinking institution founded by the child psychotherapist Dr. Stella Acquarone, greeted deMause warmly and engaged with the horrors of his material on the nature of child abuse throughout the ages. On this occasion, he received a very warm and serious response.

Not long thereafter, deMause addressed the staff members at the Portman Clinic in London – a specialist psychoanalytical centre for the treatment of forensic patients. The audience responded with tremendous sympathy. One psychiatrist exclaimed that, when she had first trained years previously, she knew nothing about child abuse and that, with the benefit of hindsight, she came to appreciate that she had overlooked the warning signs of sexual traumatisation in her patients. Certainly, she conveyed deep respect for deMause’s pioneering work in this field.

The members of the British Psycho-Analytical Society hosted an early supper for Lloyd deMause and then, afterwards, listened carefully to his lucid presentation; but, alas, in contrast to colleagues at The Parent Infant Clinic and the Portman Clinic, the bulk of the classical psychoanalytical practitioners in the room squirmed rather uncomfortably as he spoke frankly about abuse and trauma. I shall never forget that one of the attendees – a noted psychiatrist and psychoanalyst – asked deMause whether child sexual abuse at boarding school should really be considered a matter of serious concern. DeMause looked horrified at being asked such a question and replied that, in his experience, all child sexual abuse results in dreadful clinical consequences. The psychoanalyst replied that if abuse at boarding school occurred on quite a regular basis, and if all of the boys had to endure such an experience from teachers, then, surely, abuse ought to be normalised, rather than pathologised!

When deMause delivered a further paper to a gathering of the Association of Child Psychotherapists at the Tavistock Clinic, its members responded neither with appreciation (as the guests at The Parent Infant Clinic and the Portman Clinic had done), nor with denial (as one of the members of the British Psycho-Analytical Society had done), but, rather, with vitriol and outrage. One especially noted child psychotherapist screamed at deMause and berated him for having dared to present a paper filled with such ugly material. She exclaimed angrily, “I feel like you’re beating us on the head.”

The sheer range of reactions to deMause’s presentations shocked me greatly. How could a senior psychiatrically trained psychoanalyst suppose that being sodomised at boarding school might be of little consequence? One could not help but wonder whether this man had, in fact, endured such an experience during his own youth. And how could one of the United Kingdom’s most distinguished child psychotherapists feel beaten up, simply because a visiting scholar had shared his research on the history of child abuse? One would have thought that a child mental health professional would already have developed a sufficiently protective state of mind to tolerate hearing about such cases.

In discussing this situation with my esteemed colleague, Dr. Valerie Sinason, I came to appreciate more fully that, back in the 1970s and 1980s, and even into the early 1990s, most British mental health workers simply did not study child abuse as part of their clinical trainings. Indeed, when Sinason practised as a child psychotherapist at the Tavistock Clinic in the 1970s, many of her colleagues refused to believe her when she reported stories of child sexual abuse, which her patients revealed. Quite a number presumed that the child patients in question must have suffered from erotic delusions of some sort or from oedipal fantasies.

It saddened me greatly that deMause had to tolerate such resistance from senior mental health professionals, especially after he had flown several thousands of miles across the Atlantic Ocean.

Happily, I managed to invite deMause back to London approximately fourteen years later, in 2006, having arranged for him to deliver The Fifth Annual Donald Winnicott Memorial Lecture, sponsored by The Winnicott Clinic of Psychotherapy. By this point in time, mental health practitioners had become infinitely more skilled at processing and handling abuse cases; and thus, on this occasion, when deMause spoke about the status of child abuse in the United Kingdom, no one offered a single defensive or snarky comment. In fact, he received a deeply appreciative reception from a very sophisticated and responsive audience.

Throughout his career, Lloyd deMause had to endure an enormous amount of suspicion, especially during the early days, as he became the unwelcome messenger who alerted us to the awful realities of abuse and its grotesque consequences, both clinically and globally. In this respect, he offended many people simply because he told the truth. Although deMause never practised psychotherapeutically per se, his work as an educator, about the realities of child abuse, will, I suspect, have informed generations of younger clinicians, myself included, many of whom will have endeavoured to do our best to help survivors of childhood cruelty to lead more peaceful, protected lives.

I deeply regret that, in this context, I cannot provide a fuller and more detailed analysis of deMause’s many contributions to childhood history, to the study of political psychology, and to so many other fields of applied psychoanalytical scholarship. But I hope that this short tribute will, at the very least, remind colleagues of the huge contributions of this remarkable genius and kindly man, and might, perhaps, offer a gentle nudge to us all to seek out deMause’s many inspiring books and papers. I know that I have learned as much about the practice of psychology from Lloyd deMause as I have done from reading the works of Sigmund Freud, Melanie Klein, and Donald Winnicott. I cannot think of a better way to acknowledge a man of such vision and generosity.

After a long and creative life, Lloyd deMause passed away on 23rd April, 2020, in New York City, at the age of eighty-eight years, having struggled with the challenges of Alzheimer’s Disease. His loving and long-standing wife, the psychoanalyst Susan Hein, cared for him with deepest affection, as did his three children, Neil, Jennifer, and Jonathan. Lloyd deMause will be much missed by those who had the privilege to know him. Thankfully, his blue-sky thinking and his landmark work will always endure.

References:

deMause, Lloyd (Ed.). (1974a). The History of Childhood. New York: Psychohistory Press, Division of Atcom.

deMause, Lloyd (1974b). The Evolution of Childhood. In Lloyd deMause (Ed.). The History of Childhood, pp. 1-73. New York: Psychohistory Press, Division of Atcom.

deMause, Lloyd (Ed.). (1975a). The New Psychohistory. New York: Psychohistory Press, Division of Atcom.

deMause, Lloyd (Ed.). (1975b). A Bibliography of Psychohistory. New York: Garland Publishing.

deMause, Lloyd, and Ebel, Henry (Eds.). (1977). Jimmy Carter and American Fantasy: Psychohistorical Explorations. New York: Two Continents Publishing Group / Psychohistory Press.

Fine, Reuben (1979). A History of Psychoanalysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kahr, Brett (1993). Ancient Infanticide and Modern Schizophrenia: The Clinical Uses of Psychohistorical Research. Journal of Psychohistory, 20, 267-273.

Kahr, Brett (2007). The Infanticidal Attachment. Attachment: New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 1, 117-132.

Biographical Notes on the Author:

Professor Brett Kahr is Chair of the Scholars Committee of the British Psychoanalytic Council. He is Senior Fellow at the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology in London, and, also, Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis and Mental Health at the Regent’s School of Psychotherapy and Psychology at Regent’s University London, as well as Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University. He works in clinical practice with individuals and couples in Central London.

News from our Scholars

Professor Lesley Caldwell

The Rivista di Psicoanalisi has opened a new webpage Dialogues on the website of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society (SPI).

The aim is to promote exchange among Italian and foreign colleagues on clinical and theoretical themes. The article, ‘Enchantment and disenchantments in the formation and use of psychoanalytic theories about psychic reality’ by Stefano Bolognini, immediate past president of the IPA, former president of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society ( SPI) was commented on by Nicola Abel-Hirsch, Leopold Bleger, Fred Busch, Lesley Caldwell, Paolo Chiari, Abel Fainstein, Ludovica Grassi, Ted Jacobs, and Riccardo Lombardi.

Bolognini’s article and all comments can be accessed on the SPI website. The comments by Lesley Caldwell of the BPC’s Academic Membership Committtee, are reprinted below:

It is a pleasure to engage with Stefano Bolognini’s work and its sureness of touch in approaching the fiery disputes and extreme loyalties, that, despite some loosening of the rigidities of the past, continue to plague psychoanalysis and its practitioners. We still observe our colleagues, but much more significantly, ourselves, clinging to entrenched ideas of the right, the correct way of doing psychoanalysis, of being analysts, of understanding one practice or approach (ours) as psychoanalytic.

While this should encourage a determination to think through the aspects of personal rigidity we find in ourselves as well as the instances that provoke them, Stefano points to how often it seems to produce a further petrifying of thought processes, and a refusal to engage with how some theoretical shift or some institutional decision by which we are initially challenged may, with time and thought, prove to be productive and enriching.

While the international dimension, about which the author displays much valuable first-hand experience, has consistently provided me with a welcome breathing space in encountering the variety, solidity and integrity of psychoanalysis, the article goes well beyond the phenomenon of individual analysts who, in their own institutes may cling tenaciously to their theories as protective shields, only to find a heady freedom in international meetings. Rather, we are invited to think psychoanalytically about our personal identifications, at home and abroad, our over-involvements and idealisations with theories and theorists, and what this may bring to our work if our analytic foundations, and our analytic selves take on dimensions of dogma, purity, correctness, inflexibility.

In further developing a field we may regard as a familiar part of what we ordinarily do as analysts, Bolognini invites us to interrogate the dismaying challenges of our own assumptions and their historical evolution, personally, theoretically, and institutionally.

I found his thoughts about the intractable presence that our theories may assume with our patients particularly arresting in its implications for the dynamics of the consulting room if/when the patient is unconsciously faced with becoming the overlooked or unsatisfactory partner, drawn into having to fit in with an analyst and her (preferred) theoretical partner. I found this idea that the space of the studio may come to embody a preferred otherness that resides in an Other, inaccessible to the patient, who thus remains always at a disadvantage, unconsciously often knowing and experiencing only exclusion, a compelling idea to think about.

Another association that reading this article led to was not only the sense of my own engagement with my preferred theories and their promulgators, but of my attachment to my own versions of them. For instance my growing interest in Winnicott, first through my analyst, then subsequently through a series of largely chance events, has left me with certain ways of reading him, so that there is the challenge on occasion that is provided by the different readings and assumptions of others. Strangely this has been most pronounced where Winnicott has been warmly received and celebrated, rather than in those gatherings where the predominant atmosphere is a kind of caricature of the person available in the texts. I can then find myself in the kind of position described by Bolognini where difference inscribes a tendency to argue for a preferred reading rather than remaining open to what more may be discovered by a differently inflected account that may seem at variance with one’s own, and yet can offer a deeper new approach to something that has become taken for granted.

From yet another association, what of a favoured author displaying what can only be described as mean, potentially cruel disparagement of a colleague, which Winnicott certainly does in a series of letters to Michael Balint, only now uploaded as additions to volume 12 in the online Collected Works . These letters, housed at the University of Essex in the Balint archive, remind us that the intensely personal choices that shape our decisions about our theoretical allegiances in psychoanalysis also involve an encounter with the person of the analytic theorist, and that areas of disillusion and disappointment are constantly threatening our professional existence and our capacity to act as the analysts we aspire to be.

My thanks to Stefano Bolognini and to the Rivista for illuminating some of the complex areas that we aim to negotiate in our work and setting off these various strands of thought as a result.

Lesley Caldwell

Honorary Professor in the Psychoanalysis Unit at UCL.

Psychoanalyst of the British Psychoanalytic Association.

European Committee member for the IPA committee on Women and Psychoanalysis (Cowap).

With Helen Taylor Robinson Joint General Editor of the Collected Works of Donald Winnicott (OUP, 2016).

Dr Zack Eleftheriadou

Dr Zack Eleftheriadou has been invited to become a Committee member of the UKCP Child Faculty & College of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapies, Parent-Infant Psychotherapy subcommittee, chaired by Dr Yvonne Osafo. The group was set up to raise the profile of infant-parent psychotherapy in the UK and has been meeting regularly to develop formal psychotherapy training standards. The group was officially launched with a special event on April 12th 2020.

She has also been invited to offer a guest seminar in Oct 2020, entitled Transcultural supervision’ for the ITSIEY Reflective Supervision training in Infant Mental Health (0-24 months): ‘Holding the supervisee, child and family in mind’ at the Anna Freud Centre.

Dr David Henderson: Comparative Psychoanalysis Research Group

The Department of Psychosocial and Psychoanalytic Studies, University of Essex has established a Comparative Psychoanalysis Research Group. The ambition is to upgrade the group to a Centre in 2021. The work of the Research Group focuses on the study of controversy and dialogue in psychoanalysis. Intellectual, personal and institutional conflict is endemic in the history of psychoanalysis. Alongside this there are creative efforts to establish understanding and communication between perspectives.

The work of the Centre includes historical reassessment, conceptual clarification, clinical exploration, reflection on the future of psychoanalysis and attempts to articulate the conditions for fruitful dialogue:

- The fierce fights within the movement are therefore part of the essential character of psychoanalysis and the necessary means of articulating its radical content. (Bokay) Academics of the Group are engaged in re-examining and re-evaluating some of the key conflicts within the history of psychoanalysis, including the Freud/Jung split, the Controversial Discussions, the regulation of practitioners and debates about neuropsychoanalysis.

- Controversy is the growing-point from which development springs but it must be a genuine confrontation and not an impotent beating of the air by opponents whose differences of view never meet. (Bion) Attempts at dialogue between schools of psychoanalysis are often hampered by mutual ignorance. Participants are often unable to account for the vertex of their own approach. The Group engages in close readings of key texts in order to clarify common ground and genuine points of difference between schools of psychoanalysis.

- In spite of its tremendous impact on mankind, paradoxically enough, it has not yet been possible to place and classify psychoanalysis within any of the existing fields of knowledge. (Grinsberg) What kind of activity is the practice of psychoanalysis? What is it to be in analysis? What is the relationship between the privacy of the analytic couple and the claims of knowledge? Is clinical experience communicable across schools of psychoanalysis?

- An interest in apophasis (unknowing) is emerging in psychoanalytic writing. Is it possible that a recognition of the apophatic, contemplative nature of psychoanalysis could provide a way through some of the current theoretical, institutional, cultural and clinical impasses in the field of psychoanalysis? (Henderson) Is there a tension between the internal genius of the analytic attitude and the social pressures for psychoanalysts to contribute to the wellbeing of society? How can psychoanalysis negotiate the demands of the accountancy culture and the demand to just listen to the patient?

The Comparative Psychoanalysis Research Group explores the conflict and dialogue present within the analytic encounter, between schools of psychoanalysis and between psychoanalysis and society. It will run seminars, lectures and conferences. The Group’s webpage can be found here.

The Group will be holding an inaugural meeting on Wednesday, 01 July on Zoom. We will be discussing a paper by Ricardo Bernardi, ‘The Need for True Controversies in Psychoanalysis: The Debates on Melanie Klein and Jacques Lacan in the Rio de la Plata,’ International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 2002, 83 851. If you are interested in attending please contact David Henderson.

For further details about the Group’s activities contact the organiser, David Henderson, PhD.

Dr Jacob Johanssen: Social Media in Times of Coronavirus: A Paranoid-Schizoid Pandemic?

Our world is split. Both online and everywhere else. Psychoanalysis can explain some aspects of the split. Find out more here.

Dr Theodora Thomadaki: How to Look Good Naked ‘On the Couch’

Thomadaki, Theodora (March 2019) Getting Naked with Gok Wan’: A psychoanalytic reading of How To Look Good Naked’s transformational narratives. Clothing Cultures, 6 (1) :115-134 https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/cc/2019/00000006/00000001/art00007;jsessionid=bhi0a2ktcndke.x-ic-live-02

Gok Wan’s television fashion series How To Look Good Naked (Channel 4, 2006‐10) has vividly revolutionized the self-improvement genre. By developing a playful, caring and female-friendly makeover platform that values the articulation of emotional experiences in relation to the body, the series facilitates the exploration of the inner layers of subjectivity through the psychological exercises and self-reflective practices that Gok Wan sets out for his subjects. Playful mechanisms of creativity are central to his makeover practice, integrating fashion techniques and stylistic practices to encourage his female participants to reflect upon and make sense of their emotionally troubled experiences in relation to the body. Makeover props belonging to his female subjects play a fundamental role in activating a process of self-reflection and exploration of the self through relatedness. Through the close textual analysis of How To Look Good Naked (Series 2 Episode 6), this article applies Donald Woods Winnicott’s psychoanalytic ideas (1957, 1963, 1960, 1971), to argue that the creative dimensions of Gok Wan’s makeover technique reveal an object relating psychoanalytic process that entails a form of therapeutic playing; one that allows his female participants to restore aspects of self in relation to the body and to gain an emotional awareness of these experiences that leads eventually to self-discovery and self-acceptance. Ultimately, this reading of Gok Wan’s method confirms the emotional and cultural value of makeover narratives to generate rich opportunities that enrich notions of inner-self experience.

Thomadaki, Theodora (June 2017) Gok Wan ‘on the couch’: Psychoanalytic perspectives on programme strategies and personal experience in How to Look Good Naked. Free Associations: Psychoanalysis and Culture, Media, Groups, Politics,18(1):96-117 https://www.pep-web.org/document.php?id=fa.018a.0096a

How to Look Good Naked positions Gok Wan as a highly empathetic media figure in popular media. Having a first-hand experience in dealing with body-image discontent and low body-confidence, Wans highly empathetic approach towards his subject’s body-image concerns derives from his own earlier personal experience in dealing with weight struggles and eating disorders. This paper explores how the processes of emotional development depicted in How To Look Good Naked bring to the surface Gok Wan’s own unresolved experience with his body-related struggles. The crucial role of the show’s emphasis on the mirror sequence in enabling this reading is examined in detail. This article makes use of the work of Donald Woods Winnicott, and also Melanie Klein’s object relations theory, applying their ideas to selected episodes of How to Look Good Naked in order to raise the question of what is at stake emotionally for the makeover expert in his work on the programme. The article also discusses the themes that recur in media narratives created by Gok Wan around his persona, exploring how his personal experience is echoed in the television strategies and formats popularised in the show.

Professor Candida Yates: Special Issue of Free Associations: ‘Psychosocial Reflections on 50 Years of Cultural and Political Revolution’

This work, co-edited with Professor Barry Richards and Dr Alexander Sergeant, came out of the Association for Psychosocial Studies biannual conference that we hosted at Bournemouth University in 2018. Authors include: Carla Penna, Marilyn Charles, Lita Crociani-Windland, Mica Nava, Joanna Kellond, Barry Richards, Alexander Sergeant, Candida Yates.

Free Associations is an open access journal and you can read the journal articles by clicking on the links below and downloading the pdfs. The special edition includes articles by several BPC Scholars.

Contents:

- Psychosocial Reflections on Fifty Years of Cultural and Political Revolution: Editors’ Introduction

Candida Yates, Barry Richards, Alexander Sergeant - The Causes of Sanity

Barry Richards PDF - From ‘Cultural Revolution’ to the Weariness of the Self: New Struggles for Recognition

Carla Penna - Borderline: A Diagnostic Straitjacket?

Marilyn Charles PDF 50-65 - Looking Back: ‘1968’, Women’s Liberation and the Family

Mica Nava PDF - The Reproduction of Mothering: Second Wave Legacies in Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?

Joanna Kellond - Hobbits on the Wall: The ‘Frodo Lives!’ Campaign as Psychosocial Symbol

Alexander Sergeant - Masculinity, affect and the search for certainty in an age of precarity

Lita Crociani-Windland, Candida Yates

Caroline Zilboorg

Caroline Zilboorg has created a website to accompany the publication of her two-volume biography about her father, the psychoanalyst Gregory Zilboorg. It contains a profile of the forthcoming biography and a bibliography of Gregory Zilboorg’s work. You can access the website here.

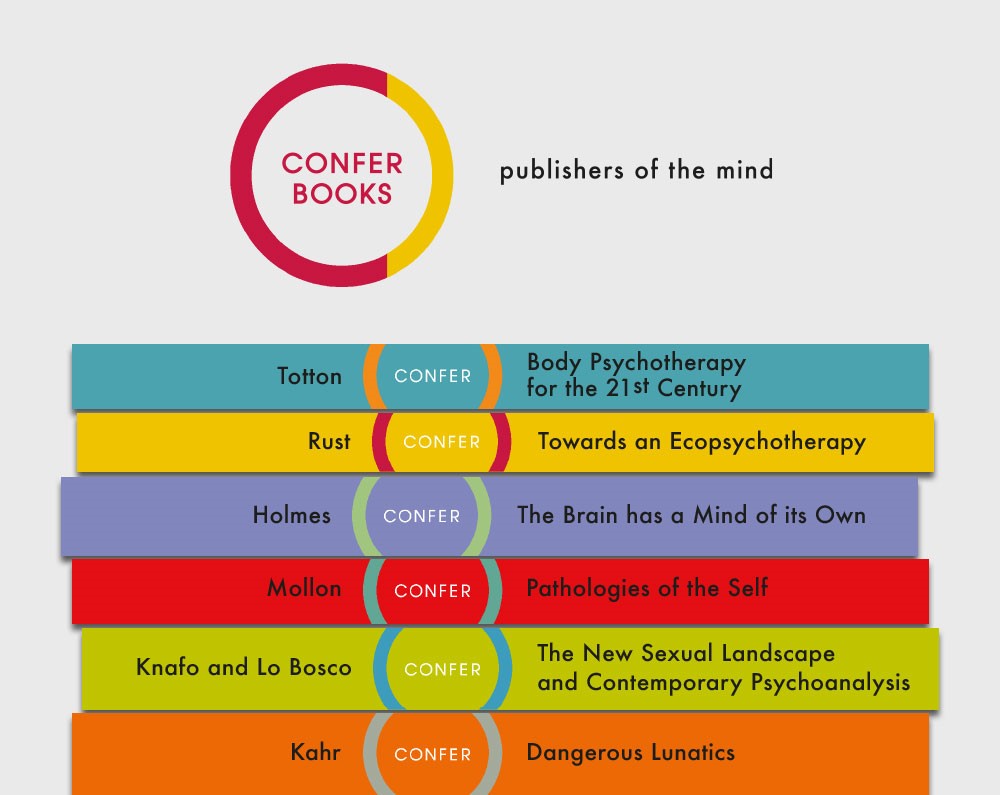

Confer Books

Confer Books has published the first six books and several of the authors are linked to the BPC. You can find the complete list here.

Association for Psychosocial Studies (PCS)

APS are planning a series of virtual events over the summer 2020.

Like everyone, APS members are working under very altered and potentially isolating circumstances and it was with great regret that we had to postpone our 2020 conference on The Psychosocial Body at the beginning of June. However, we believe that psychosocial thinking is needed more than ever in these times and we have therefore devised a free online programme. APS are planning a series of events over the summer 2020. Please check back for confirmed dates and more information.

APS and the Journal of Psychosocial Studies Online Reading Group

Please join us for our second in a series of monthly online reading groups where we will be coming together and discussing topical articles drawn from the Journal of Psychosocial Studies. These reading groups are free to attend and open to all. The reading group will be held on the last Friday of every month, 5pm to 7pm. All registered attendees will be sent a link to join a Zoom call before the event.

For more upcoming events and details, please see here.

Association for the Psychoanalysis of Culture & Society (APS): Annual Conference and Journal

Several BPC Scholars are involved in the Association for Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society (Marilyn Charles, Michael O’Loughlin, Angie Voela and Candida Yates).

APCS holds an annual conference. This year’s theme is Truth and Dare:

Complexities in the Psychosocial Space. In recent years we have met in the intimate setting of the Rutgers Inn and Conference Center on the campus of Rutgers University in New Jersey, U.S.A. This year due to the uncertainty and constraints caused by the global Covid-19 pandemic the conference will be held online.

This conference will now be held online over two weekends; October 17-18 and 24-25, 2020. Details about online platform will be announced closer to the time and posted on the APCS website.

In September 2020, Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, the official journal of the APCS will publish a special issue on Contemporary Ireland, edited by Michael O’Loughlin, Ray O’Neil and Carol Owens. In this issue, authors bring diverse psychoanalytic lenses to bear on literary, political, clinical, and autobiographical aspects of the subject of Ireland.

To celebrate the centenary of the publication of Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle PCS is hosting a special issue (December 2020) edited by Rosaura Martinez (Universidad Nacional Autonoma di Mexico) with contributions from the New School (NY, USA) event ‘What after Beyond…? On Freud’s Death Drive and the Future of a Better World’.

The following special issues are in progress:

- Psychoanalysis, Sexualities and Networked Media, edited by Jacob Johanssen (St Mary’s University, UK). This special issue takes psychoanalytic theories of sexuality / sexualities and how they were adapted and critiqued by other disciplines as a starting point for analysing contemporary networked media, online spaces and digital phenomena.

- Trauma and repair in the museum, edited by Alexandra Kokoli (University of Middlesex, UK) and Maria Walsh (Chelsea College of Art, UK); This special issue focuses on the unconscious roots and ramifications of museological origins, histories and practices, addressed through clinical and academic perspectives.